Extinction crisis

Time to act

The diversity of life is the defining feature of our planet. It's in catastrophic decline. Crying wolf? Unfortunately not.

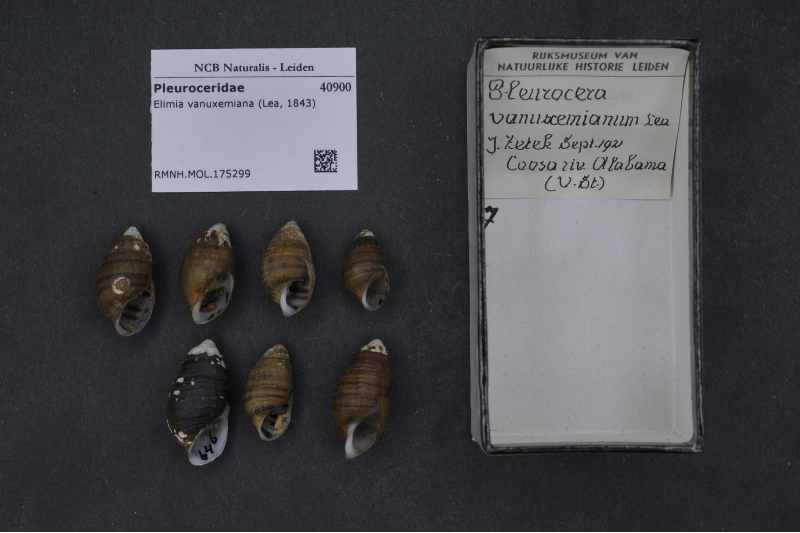

Gone forever...

Here are just a few arbitrary examples of precious genomes lost forever. Each one played a role in its ecosystem, which after losing it changed irreversibly.

Extinction is forever. Losing a species means also losing its role in its ecosystem. If it happened to be a critical (keystone) species, cascading effects will completely degrade and transform the habitat. Birds, mammals and other vertebrates have lost more than 50% of their populations in the last 50 years. Some evidence suggests that plants and insects are declining just as quickly. Although this collapse in slow motion has catastrophic consequences for life on Earth, it receives little public attention. But it must be urgently addressed.

Biodiversity in freefall

Our needs are degrading natural ecosystems a lot faster than we can research them. The collateral damage is immense - and it's very likely as big a threat to life than climate change.

Endangered Titan Arum, Amorphophallus titanum, Western Sumatra.

Black-naped monarch, Hypothymis azurea. South-east Asia.

Coral colony, Red Sea, Egypt.

Endangered Titan Arum, Amorphophallus titanum, Western Sumatra.

It’s simply stunning: the decline in abundance of vertebrates (fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals) exceeds 50% in the past 50 years! The estimate is less clear for plants, fungi and for invertebrates. However, some evidence suggests that plants and insects are declining just as quickly as vertebrates do. Invertebrates include protozoa, sponges, polyps, flatworms, roundworms, annelids (e.g. earthworms), echinoderms (e.g. starfish, sea urchins), molluscs and arthropods (e.g. insects, crustaceans, spiders, millipedes). It’s these life forms (plus plants and fungi) that generally form the backbone of ecosystems. Losing them means also losing the interactions between these species: the ecosystems become dysfunctional. Although extinction of species is a natural phenomenon, it currently happens 1’000 to 10’000 times faster than the background rate of extinction known from evolutionary history. It has two fundamental causes, tabooed in public discourse: the exponential increase in both the number of humans and their insatiable desires.

%2C%20New%20Caledoni.jpg)

Species collapse in slow motion

Thousands of species survive only in a few tiny populations which are at high risk of vanishing.

Losing species is like going bald. At first everything seems normal. The hair just gets a little thinner. But then it stops growing back. In species heading for extinction, the number and density of populations declines first, while the species is still observable. Then, more and more thinned-out populations disappear. Before it dies out, the species may persist for a while, unable to reproduce and functionally extinct. Even under normal conditions, life in the wild is a walk on knife’s edge. It takes only a few unfavourable factors combined to drive a species over the edge – slowly, but surely. That’s especially true if the evolutionary adaptation simply can’t cope with the required speed of change. The deceivingly normal appearance of disintegrating ecosystems and the almost imperceptible loss of species are among the biggest challenges in conservation.

Kagu (Rhynochetos jubatus). Endangered. New Caledonian endemic, almost flightless. Single species in its own family. EDGE rank 12 of 662 birds. Over 38 million years of threatened evolutionary history. Global population 250 to 1000 individuals, declining due to introduced predators.

Stopping extinction — can we manage?

The relentless growth of the human population is causing ever more profound damage to ecosystems. Watching and waiting is not an option. We must act now.

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), the famous Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician, coined a simple but non-trivial thought that could be used as both an ethical and ecological guideline for dealing with nature: "We are life that wants to live amidst life that wants to live." But that’s not how we face the biosphere. Quite the contrary, we are causing the sixth mass extinction in the 4-billion-years history of life on Earth. Each of the previous five was the result of an astronomical event with global implications. This time we are the disaster. It means the loss of thousands of species. Forever. Each of them is a unique solution to the challenges of survival and a handbook for fitness in natural selection. But what is the benefit of a particular species? Well, that's a completely wrong question. The diversity of life is essential to both the functioning and resilience of the biosphere and its ecosystems. In contrast, the "utility" of a species to humans is completely irrelevant to the functioning of life. Nature - in its wild state - is the optimized result of millions of years of co-evolution of myriads of organisms. We cannot improve it, and certainly not by destroying functioning ecosystems. The extinction crisis caused by us is an even larger threat than climatic change to the biosphere, and aggravated by it. Any species whose reproduction rate can no longer compensate for losses is driven to extinction sooner or later — individual by individual, population by population. In this gradual, often imperceptible way, we are risking the irreversible degradation or disintegration of numerous ecosystems. Worse even, the extinction of any species is irreversible for the entire future of mankind. The development of a species takes tens of thousands, often hundreds of thousands of years. Once lost, it is gone forever. Although new species do arise and new ecological niches do develop, no human will ever see the gaps ripped open by extinction closed again. So how could we ensure that the wild survives? We must allow it to coexist with us. This requires keeping a major portion of land and sea wild. The UN Convention on Biological Diversity proposes 30%. And this should be achieved by 2030... That's a sprint to start a marathon. Currently only 17% of terrestrial and 8% of marine areas are under some protection. And often this protection is more theoretical than real. In addition, key drivers of extinction must be brought under control. These include habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, (human) population growth, and overharvesting. In plain text: us. More precisely, the excessive number of humans and the excessive needs we expect to see satisfied, at the expense of other life. Life which has nothing to match our ability to cooperate through language and the resulting behavioural, cognitive and technical developments, including advanced tools of mass destruction of other life, including other humans. We can outcompete practically all other life forms. The problem is: the effects on the biosphere are devastating. And destroying countless species and ecosystems will ultimately backfire. Overfishing, overhunting, deforestation and pollution have long ago started to take their toll. To leave this ruinous path, we must learn to optimize, not maximize our use of nature. At the root, this also means optimizing, not maximizing our goals.

The catch of having no match

Key drivers of extinction must be brought under control

Today's species extinction is the result of the rapid increase in the number of people and their demands. Both lead to the fragmentation of habitats, overuse, pollution and the spread of invasive organisms and pathogens.

The root cause of the extinction crisis can be named in 6 words: too many humans, too many demands. These two are largely tabooed, including in many international organizations. Yet they have severe consequences: • Expanding the exploitation of land and sea, especially for food • Direct exploitation (building settlements and traffic lines, cutting forests, ploughing grasslands, overfishing the oceans) • Climatic change (a slower but growing impact) • Pollution • Invasive species and pathogens spread by human activities A key driver of biodiversity loss is our food system, notably the extremely high land use for livestock bred for (excessive) meat consumption. Another key cause for losing species is human-made fragmentation of habitats. The smaller and less connected a habitat, the fewer species it can sustain. This connection is logarithmic (and dependent on the type of ecosystem and the type of species). A 50% reduction of viable habitat results in a roughly 10% loss of species; a 90% reduction of habitat in a 50% loss of species.

30x30: Optimal, not maximal use of nature

The UN's Global Biodiversity Framework calls for effectively protecting 30% of the world’s terrestrial, inland water, coastal and marine areas by 2030 in order to effectively contain the biodiversity crisis.

Although climate change dominates the headlines, in the background governments have also started discussing the extinction crisis. Current policy responses try to address food through intensive agriculture, biodiversity through protected areas, and climate change through reducing emissions. In 2023 the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) met in Montreal, adopting the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework as a shared international roadmap out of the ecological crisis. This ambitious commitment includes 23 targets aimed at reversing habitat and species loss. Target 1 calls for planning and managing all areas on the planet to bring the loss of areas of high biodiversity importance close to zero by 2030, while respecting the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities. Target 2 calls for restoring 30% of all degraded ecosystems by 2030. Target 3 (“30x30”) calls for effectively protecting 30% of the world’s terrestrial, inland water, coastal and marine areas by 2030. At present only about 17% of terrestrial and 8% of marine areas are under some form of protection, which often may not be truly effective. Target 4 calls for halting species extinction, protecting genetic diversity and managing human-wildlife conflicts. 30x30, as well as the entire Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, is an immensely positive development and a huge commitment, but it won’t be achievable unless people at local, regional, national and international levels begin to understand and endorse the prime value of intact ecosystems and thus their species. To ease the relentless pressure on other life, we must also learn to reduce and reverse disturbance and further degradation of already impoverished ecosystems, and to reconnect these remnants to increase their viability for other species. Given the prevailing anthropocentrism, this is a huge challenge. In the long term, however, we need to also address our own numbers and needs. Clearly, 10 or 12 billion top predators on Earth are too many. They put the trophic pyramid upside down, creating massive ecological and ethical fall-out. We offer no cheap advice on how to tackle this immense problem. However, tabooing it belies its existential nature, enormity and pervasiveness.